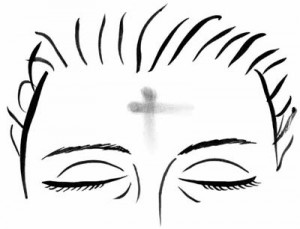

Jesus, when questioned by the Pharisees about calling upon tax collector Matthew to be his disciple, replied, “Those who are well do not need a physician, but the sick do. Go and learn the meaning of the words, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ I did not come to call the righteous but sinners.” (Mt 9:12-13) This gospel verse came to mind, lo and behold, just as I was leaning toward giving up and taking on the same old things for Lent this year—and those words of Jesus sent me straight back to the drawing board to ask myself annoying questions, like: “What’s wrong with my same old things?” and “Isn’t it good to give up a food I like, pray better, fill the Rice Bowl?” and “Is this the best I can offer my Lord?”

Of course my same old things are worthy of practicing during Lent, and I do have others on my list. But I know deep down that I probably hang onto those same old things because they’re tried and true; I do them because I do them well and easily. For me, it’s no big deal to ignore chocolate for 40 days, or mumble through prayers as I multi-task, or transfer the change jar into the Rice Bowl.

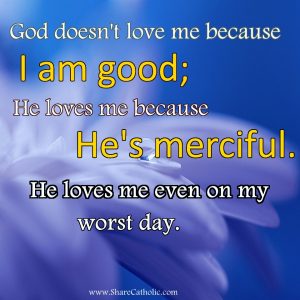

And therein lies the problem, I guess: My same old things are too easy, too natural, too painless to feel much like sacrifice. Chocolate and rote prayer and parting with loose change just aren’t things for which I require medicine or a physician. Shouldn’t I be asking, then, for the sake of my Lenten journey this year, “What areas of my life are in need of mercy—whether God’s mercy upon me, or mine upon another person? What areas are making me sick, even if I don’t recognize the symptoms? What areas are keeping me from hearing the call of Jesus?”

To be sure, there’s a wealth of Lenten books and other resources that can enhance one’s spiritual journey toward Easter. I especially like those clever little lists of suggested sacrifices that take all the heat off our own planning and creativity.

But I know, once again deep down, that the greatest resource is my own conscience. It’s that inner room I enter and exit a thousand times a day, whether by choice or necessity, as I interact with others, tend to my work and errands, or indulge in leisure. It’s where the ultimate physician dwells in infinite patience, with his life support of Holy Spirit, while out in the world I flounder—in a seeming fever of faithfulness that spikes and breaks—between longing to please him and fearing what he might ask of me today, for Lent, and for every tomorrow beyond.